Expand all

Collapse all

Overview

Acne vulgaris is a common skin condition that typically starts during puberty and is experienced by most teenagers, for some it lasts into the third decade of life (Lavers, 2014). Acne may be mild to severe, and can have a severe impact on a person’s mental, physical and social functioning at a critical time in life. It demands a holistic, biopsychosocial approach to care.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Aetiology

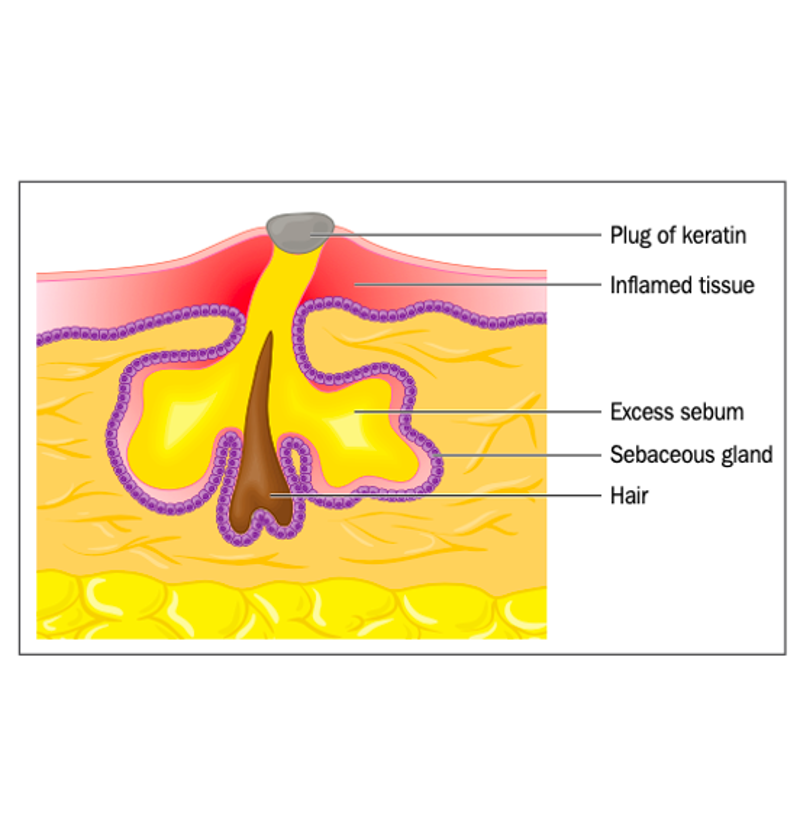

Acne is a disorder of the pilosebaceous units, caused mainly by increased sebum secretion and plugging of follicles (Figure 1). The bacterium Propionibacterium acnes exacerbates the problem but is not the principal cause. The initial trigger for acne is the androgen hormone. There is a genetic predisposition, and often a family history of the problem.

Drugs such as corticosteroids, hormones, anticonvulsants and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can trigger flares (Oakley, 2014). Occlusive cosmetics and polycystic ovary syndrome are also associated with acne.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Symptoms

Acne appears mainly in areas of the body where there are more sebaceous glands, such as the face, back and chest.

NICE (2021) classifies acne by severity:

- Mild: predominantly non-inflamed lesions (open and closed comedones) with few inflammatory lesions (Figure 2)

- Moderate: more widespread with an increased number of inflammatory papules and pustules (Figure 3)

- Severe: widespread inflammatory papules, pustules and nodules or cysts (Figure 4). Scarring may be present.

Patients can have a mixture of inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions at different stages of formation. Lesions last for days, weeks or months (Table 1). Once the acne has cleared, scarring may have as much of an impact on the patient as the acne.

|

Table 1. Types of acne lesion |

||

|

Lesion types |

Description |

|

|

Non-inflammatory |

Closed comedone (whitehead) |

A blocked follicular papule |

|

Open comedone (blackhead) |

An open follicular papule with surface pigment-melanin |

|

|

Inflammatory |

Papule |

A raised red lesion <1cm |

|

Pustule |

A raised | |

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Diagnosis

Comedones must be present for a diagnosis of acne (NICE, 2021). Patient assessment should include a medical history and a consideration of past acne. Examine the face, chest and back, and record the number and type of acne lesions, skin changes and any scarring (Van Onselen, 2017).

Referral

NICE (2021) recommends referral for specialist assessment and treatment where:

- Mild-to-moderate acne is unresponsive to two courses of treatment

- Moderate-to-severe acne is unresponsive to treatment including an oral antibiotic

- There is scarring or persistent pigmentary changes

- Symptoms cause persistent psychological distress.

Endocrinology referral should be considered for patients with acne who also have clinical features of polycystic ovary syndrome, such as menstrual irregularity and hirsutism (NICE, 2021).

Urgent, same-day referral for assessment within 24 hours by the on-call hospital dermatology team is required for acne fulminans, a sudden severe inflammatory reaction that precipitates deep ulcerations and erosions, sometimes with systemic

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Management

Patient education

It is important that patients are informed and encouraged to adopt the following into their activities of daily living:

- Wash the face twice a day in lukewarm water with an acne wash. Avoid rubbing or scrubbing, and pat dry (Bowser, 2010)

- Apply a light, oil-free, non-comedogenic moisturiser or antibacterial lotion (with SPF in the summer months)

- Use non-comedogenic make-up and a light foundation

- Before shaving the face, apply an acne wash and use a light moisturiser as a shaving lotion. A wet shave with a single blade razor is preferable, as a dry shave will traumatise the lesions

- Avoid picking spots as this leads to scarring (Table 3)

- Use moisturisers that do not block pores. Many products now have non-comedomic agents.

Mild acne

1. Benzoyl peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide this is a potent bactericide that reduces Propionibacterium acne colonisation (Well, 2013). It is used in mild-to-moderate acne.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Resources

Resources |

|

|

British Association of Dermatologists: |

https://www.bad.org.uk/for-the-public/patient-information-leaflets/acne |

|

Primary Care Dermatology Society |

https://www.pcds.org.uk/ |

|

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries |

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/acne-vulgaris |

|

DermNetNZ |

https://dermnetnz.org/ |

|

Talk Acne patient support |

https://www.talkhealthpartnership.com/talkacne/ |

References

Baker A. Treatment of a 25 year old female patient with moderate acne vulgaris. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. 2014;3(1):28–33. https://doi.org/10.12968/joan.2014.3.1.28

Bowser A. Acne and Rosacea: The Complete Guide. London. Vermilion; 2010.

Chien AL, Qi J, Rainer B, Sachs DL, Helfrich YR. Treatment of Acne in Pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(2):254.

Lavers I. Acne vulgaris—diagnosing management and optimising patient care. Dermatological Nursing. 2014;13(14):16–25

Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb02521.x

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Acne vulgaris. Revised June 2021. http://cks.nice.org.uk/acne-vulgaris (accessed 11 January 2022).

Oakley A. Acne. July 2014. DermNet NZ. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acne/ (accessed 11 January 2022).

Nast A, Dreno B, Bettoli V et al. European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:Suppl:1:1-29.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.