Myeloma

Myeloma and other plasma cell disorders can present to accident and emergency departments and general physicians in a variety of different ways. Myeloma outcomes have improved dramatically over the last decade as a result of novel therapies, several of which are now commonly continued to disease relapse.

Article by SJ Chavda, K Yong, Charlotte Pawlyn and Graham H Jackson

Expand all

Collapse all

Key Points

- Multiple myeloma is a common condition and should be considered in the differential in patients presenting with bony pain and haematological abnormalities.

- Key laboratory investigations include full blood count, renal function, calcium levels, albumin, serum/urine paraprotein and serum free light chain. Imaging should also be requested such as positron emission tomography-computed tomography, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging if available.

- A diagnosis of smouldering or asymptomatic multiple myeloma requires the absence of multiple myeloma defining events including high risk biomarkers and one or more lesions on magnetic resonance imaging.

- Patients should be treated in a multidisciplinary fashion and offered participation in clinical trials if possible.

- Standard of care in young fit patients includes combination chemotherapy with novel agents (thalidomide, bortezomib, lenalidomide) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation, while elderly patients are treated with chemotherapy alone.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Overview

Myeloma is a bone marrow cancer of terminally differentiated B cells, which are antibody-secreting plasma cells. It is the second most common haematological cancer and a new diagnosis occurs in over 5700 patients in the UK each year, representing approximately 2% of all new cancer cases. Myeloma is predominantly a disease of older people with median age at diagnosis of around 70 years and as such, the incidence is increasing with population ageing. It is more common in males by a ratio of 1.4:1 and has an increased incidence in those of black ethnicity.

Myeloma aetiology has been associated with radiation, agricultural and other chemical use, and combustion fuel products such as benzene but only very rarely is an identifiable underlying precipitant found. Familial and genetic factors have been implicated and single nucleotide polymorphisms have been associated with an increased relative risk, although the difference in absolute risk is small.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Symptoms

Patients can present with a range of different symptoms from fatigue to classical CRAB (hypercalcaemia, renal failure, anaemia, bony lesions) criteria (Table 1). The diagnosis of multiple myeloma can be difficult to make, with patients visiting their GPs on average three times before referral to secondary care.

Anaemia may be accompanied by low platelet counts or more rarely low total white cell counts. Single symptoms such as back pain are often non-specific, although when coupled with laboratory abnormalities, such as leucopenia or hypercalcaemia, have a much higher predictive risk of multiple myeloma (Shephard et al, 2015). It is therefore imperative to consider a diagnosis of multiple myeloma in patients presenting with back pain coupled with haematological abnormalities or CRAB criteria. Bone disease may also present with pain in other parts of the skeleton including the shoulder, hip, sternum or limbs.

| Symptoms of myeloma – CRAB |

|---|

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Diagnosis

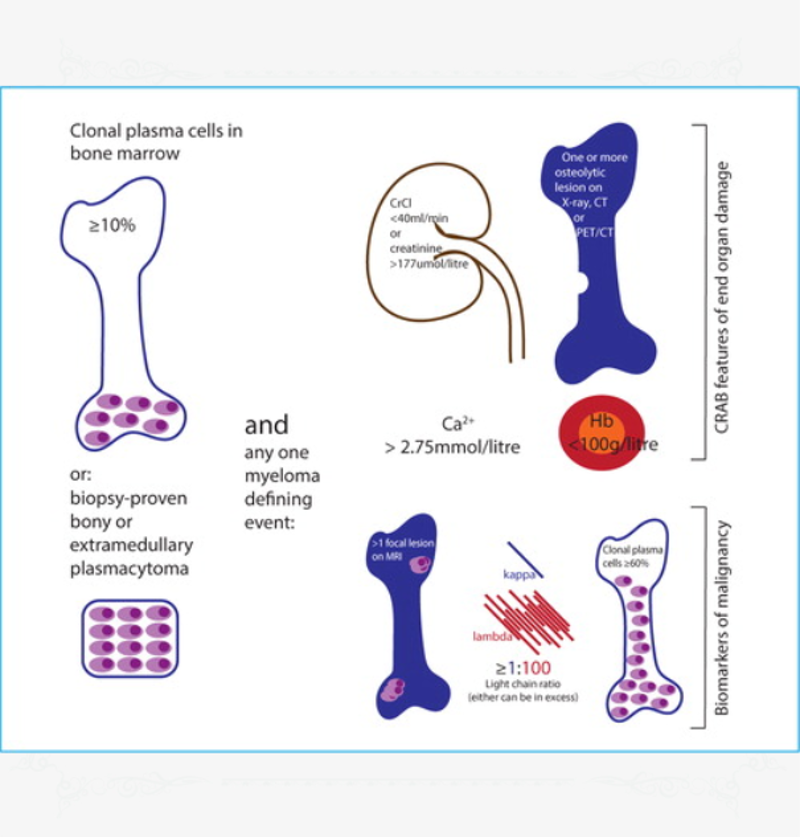

The diagnostic criteria for myeloma were updated in 2014 and the current version does not require evidence of end organ damage (Figure 1) (Rajkumar et al, 2014). The criteria now incorporate biomarkers of malignancy that suggest impending end organ damage, based on prior studies which indicated that patients with such features would have a greater than 80% chance of developing myeloma within 2 years.

In order to make a diagnosis of multiple myeloma the following investigations should be

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Treatment

Multiple myeloma is a disease with a classically relapsing remitting course. Patients may relapse with biochemical disease alone or with clinical symptoms. All patients should be treated in a holistic, multidisciplinary fashion. Patients should be given written information on their condition and introduced to a clinical nurse specialist.

All patients should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting with clinical oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, haematologists and clinical nurse specialists, and a treatment plan formulated. If possible, the patient should always be offered participation in a clinical trial. Patients may need social and psychological support as well as specialist haematology care.

Asymptomatic multiple myeloma

Patients with low risk asymptomatic multiple myeloma are actively monitored on a 3-monthly basis with a:

- clinical history

- examination

- blood tests for full blood count

- renal function

- corrected calcium levels

- serum paraprotein

- urinary electrophoresis

- urinary Bence Jones protein

- serum free light chain analysis in light chain only disease

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Resources

References

Bird J, Owen RG, D'Sa S et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:32–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08573.x

Kyle RA, Durie BGM, Rajkumar SV et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for

progression and guidelines for monitoring and management.

Leukemia. 2010;24(6):1121–1127. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.60

Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukaemia. 2009;23(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2008.291

Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of

undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple

myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5412–

5417. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-12-194241

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bortezomib and thalidomide for the first line treatment of multiple myeloma. Guideline TA228. 2011. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta228 (accessed 18 January 2022)

Nau K, Lewis W. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(7):853–859

Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos M et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma: an International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood. 2015;125(13):2068–2074.

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.