Expand all

Collapse all

Introduction

The haematological system consists of:

- blood

- blood vessels

- bone marrow

- lymph nodes

- spleen

- proteins involved in haemostasis and thrombosis.

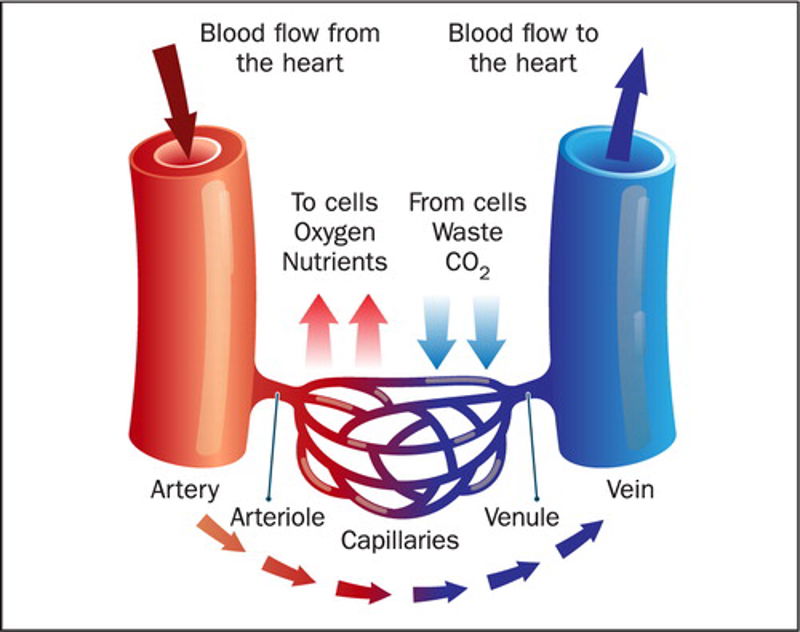

Blood circulates the human body through blood vessels (Figure 1), containing red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets suspended in plasma. Plasma is the liquid component of blood and contains a wide variety of other components, supplying the body with electrolytes, hormones, vitamins, antibodies, oxygen, and nourishment, while removing carbon dioxide, nitrogenous waste products and maintaining body temperature (Kumar and Clarke, 2017). Blood tests can be done to measure levels of these and other components in the bloods and the results are used to assist with diagnosis of many diseases when they are outside the normal range.

The formation of

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Blood cell function

White blood cells (leukocytes) are key in fighting infection and ingesting dead cells, tissue debris, mutated cancerous cells and foreign bodies that enter the blood stream, such as allergens via phagocytosis. There are several types of leukocytes which are each adapted to their own unique role. These are:

- neutrophils

- eosinophils

- lymphocytes

- monocytes

- basophils

Platelets (thrombocytes) are much smaller and are involved in blood clotting to prevent blood loss and pathogens from entering the blood stream through various coagulation pathways. Red blood cells (erythrocytes) are essential in transporting oxygen from the lungs to respiring cells in the body and taking the waste product carbon dioxide back to the lungs to be expired (Hoffbrand and Steensma, 2019). Erythrocytes are adapted for this role by having fewer organelles, to enable them to fit through small capillaries as well as creating more room for haemoglobin (Hb) – the protein that binds with oxygen to

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Blood group

An individual’s blood group is inherited from their parents and can be identified by antibodies and antigens in the blood (Hall, 2016). Antibodies are proteins in plasma that recognise foreign substances and alert our immune systems to destroy them. Antibodies identify these foreign substances by the unique protein molecules (antigens) found on their surface, which are also found on erythrocytes. There are four blood groups using the ABO system: A, B, AB and O (Table 1). However, erythrocytes can have an additional RhD antigen. Each blood group can therefore be described as either RhD positive or RhD negative, depending on whether the antigen is present or not. This gives a total of eight blood groups.

|

Table 1: Basic ABO blood group classification |

||

|

Blood group |

Antigens present on the erythrocytes |

Antibodies present in the plasma |

|

A |

A antigens |

anti-B antibodies |

|

B |

B antigens |

anti-A antibodies |

|

O |

No antigens |

both anti-A and |

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Blood tests

There are a variety of blood tests specific to haematology. For example, full blood count, which measures the size, number and maturity of the various blood cells in the sample (Table 2). Other components of blood can also be measured, including coagulation factors such as von–Willebrand factor, or factor VIII concentrate (VIII:C) (Palta et al, 2014). Abnormal results in either of these factors suggests where in the coagulation pathway the problem lies. Bleeding time, prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are all clinical laboratory-based tests performed to measure the time it takes for blood to clot. Bleeding time involves creating a standardised incision and timing the cessation of bleeding (Russeau et al, 2021). Conversely, prothrombin time involves adding reagents in a laboratory to a blood sample and measuring the time for plasma to clot. The international normalised ratio was introduced to standardise prothrombin time results (Bonar and Favaloro, 2017).

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Blood disorders

Although not exhaustive, Table 3 gives some examples of key blood components and disorders associated with them. All anaemias relate to red blood cells and all leukaemias are cancers that generally relate to white blood cells.

|

Table 3: Blood components and their associated disorders |

|

|

Blood component |

Associated disorders |

|

Red blood cells |

Anaemia of chronic disease Aplastic anaemia Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia Malaria Pernicious anaemia Thalassemia |

|

White blood cells |

Neutropenia/ agranulocytosis myeloma Neutrophil leucocytosis |

|

Platelets |

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia Immune thrombocytopenic purpura Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Plasma |

Disseminated intravascular coagulation von–Willebrand disease |

|

Blood group |

Haemolytic transfusion reaction (immediate or delayed) Transfusion-associated circulatory overload Transfusion-related acute lung injury |

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Key Points

- The key components of blood are red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma

- Each component of blood is adapted to maximise its specific function

- Blood travels in vessels to supply the body’s tissues with everything they need to facilitate life and removing waste products

- If one or more components of the blood are affected such that they cannot normally perform their role, blood disorders and disease result

For full article, please see: The basics of blood and associated disorders

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.

Resources

Bonar R, Favaloro EJ. Explaining and reducing the variation in inter-laboratory reported values for International Normalised Ratio. Thromb Res. 2017;150:22-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2016.12.007

Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. J Intern Med. 2020;287(2):153-170. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13004

Carton, J. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Pathology. (2nd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017

Cho M, Modi P, Sharma, S. Transfusion-related Acute Lung Injury. [online]; Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing: 2021

Eden R, Coviell, J. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. [online]; Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021

Hall, J. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. (13th edn). Canada: Elsevier; 2016

Hoffbrand A, Steensma D. Hoffbrand’s Essential Haematology. (8th edn). New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2019

Kruger PC, Eikelboom JW, Douketis JD, Hankey GJ. Deep vein thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management. Med J Aust. 2019;210(11):516-524. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50201

Kumar P, Clarke M. Clinical Medicine. (9th edn). China: Elsevier; 2017

McHugh D, Gil J. Senescence and aging:

To view the rest of this content login below; or read sample articles.